Situated in grandiose surroundings and buildings in Bloomsbury, it seems to epitomise both the indomitable curiosity that has so for long been part of the country’s character, and the desire to innovate and look forward that has seen so many inventions and ideas originate from this nation.

Of all the collections and institutions in Britain, perhaps none have so tight a grasp on the national consciousness – and indeed its affections – as the British Museum.

Yet its development has not been as straightforward or an easy one. It has battled – and, in one notorious case, continues to battle – international controversy, and its inability (like all over national collections in Britain) an admission fee means that a valuable source of revenue is not open to it.

Its continued pre-eminence both in this country and overseas is a testament not just to the excellence of its displays and exhibitions, but the visionary men and women who have developed it from its foundation in 1753.

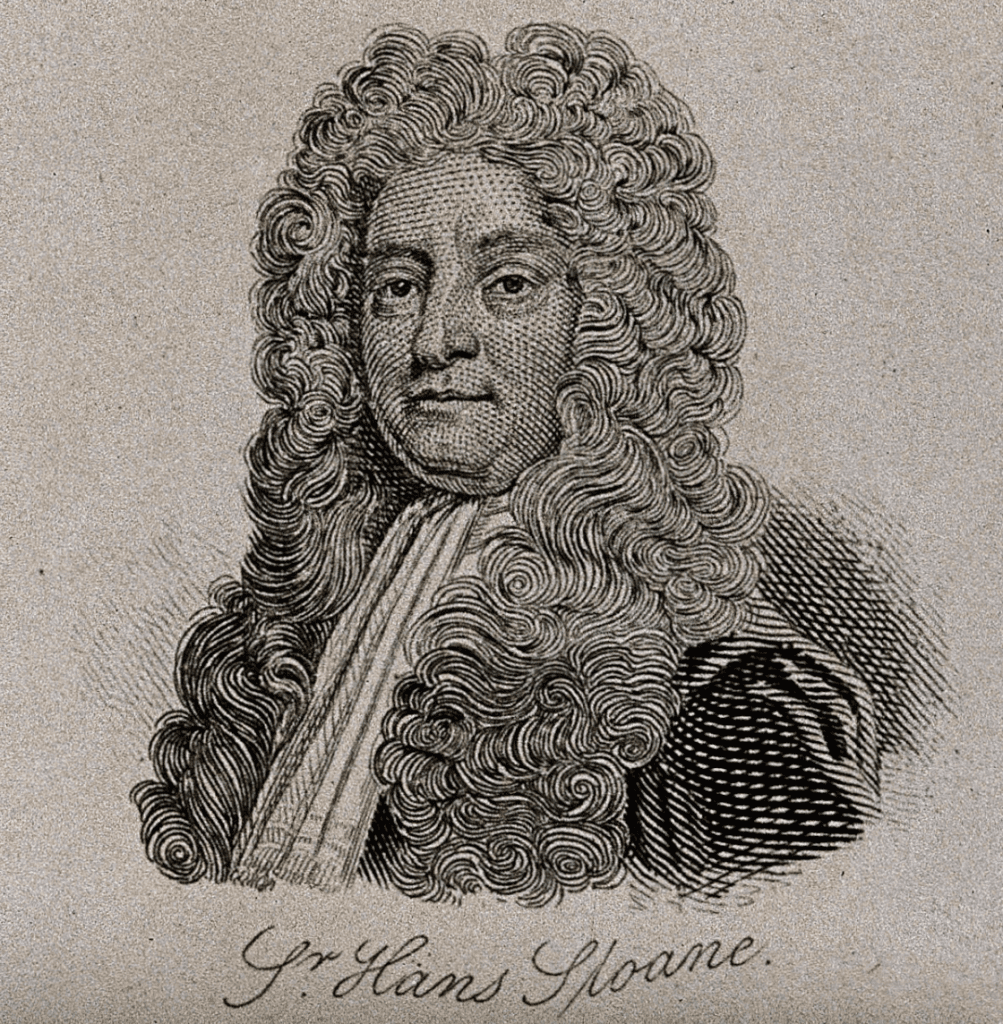

The first man who helped to implement the museum was Sir Hans Sloane; in partial acknowledgement of his many achievements, Sloane Square in Chelsea is today named after him.

He was a collector of natural objects, and decided upon his death to sell his impressive horde of artefacts to the nation; they were acquired in the name of the then-king George II for £20,000.

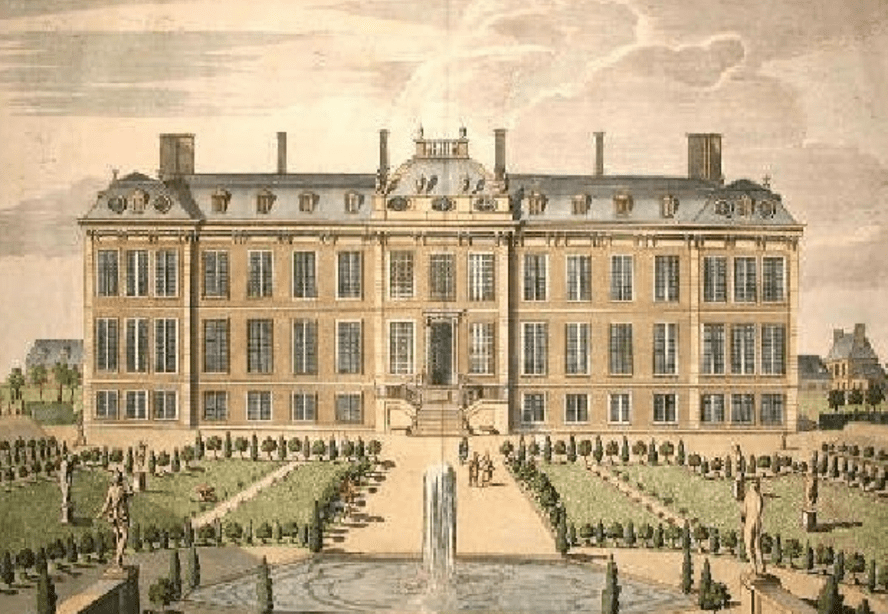

It was thought that a suitably imposing building was needed to house Sloane’s collection of 71,000 objects and so a late 17th century mansion, Montagu House, was acquired for the purpose.

Another proposed location, Buckingham House, was rejected; it eventually became what we know as Buckingham Palace.

Buckingham Palace, London.

It officially opened on 15 January 1759, buoyed by the king’s gift of the Old Royal Library, and swiftly became a phenomenon. The British Museum as originally conceived consisted of everything from books and manuscripts to botanic and antique samples taken from the Far East and the Americas.

Previously, most British collections had been in the gift of either the king or the church, and thus had felt faintly forbidding. Now, this new style of institution was the first national collection, meaning that everyone visiting felt that he or she had a stake in the priceless objects on display.

These included rare manuscripts such as the only surviving manuscript of Beowulf and an early copy of the Lindisfarne Gospels, and it soon became extremely fashionable to donate items of great personal or national value to the collection.

These included the actor David Garrick’s private library, Sir William Hamilton’s assemblage of early Greek vases and Captain James Cook’s display of items from the South Seas; as each new wonder beguiled the London public, it became clear that the British Museum had a place in the national heart that was only, perhaps, rivalled by the monarchy.

With the continued expansion of the collection, it soon became clear that Montagu House was unfit for the purpose of housing a large and growing museum, and so, after George IV donated the King’s Library in 1822, an entirely new building was planned and constructed.

Montagu House

The famous library building was designed by Robert Smirke, and the Reading Room that followed was the creation of his younger brother, Sydney. As time went on, the neo-classical building grew and expanded throughout Bloomsbury, and some of the collections had to find other homes.

This resulted in the foundation of the Natural History Museum in Kensington in the 1880s, and, more recently, the establishment of the British Library, initially as a self-contained entity that remained in the museum, and, since 1997, housed in its own premises in St Pancras.

The Natural History Museum

The nineteenth and twentieth centuries helped burnish the museum’s reputation, with visitor numbers increasing decade by decade, and various actions taken to make it more accessible; the first guide was published in 1903, and the first permanent lecturer appointed in 1911. Throughout the 20th century, the sense of innovation and looking forward was a continual part of the museum’s mission, helped by sound common sense. At the outbreak of war in 1939, it was feared that the priceless collections might be in danger from bombing, and so were dispersed throughout the country; this proved a wise move, as the Duveen Gallery was indeed hit by a bomb and badly damaged. Its treasures were distributed to a variety of unlikely places, including Aldwych tube station and a quarry in Wales.

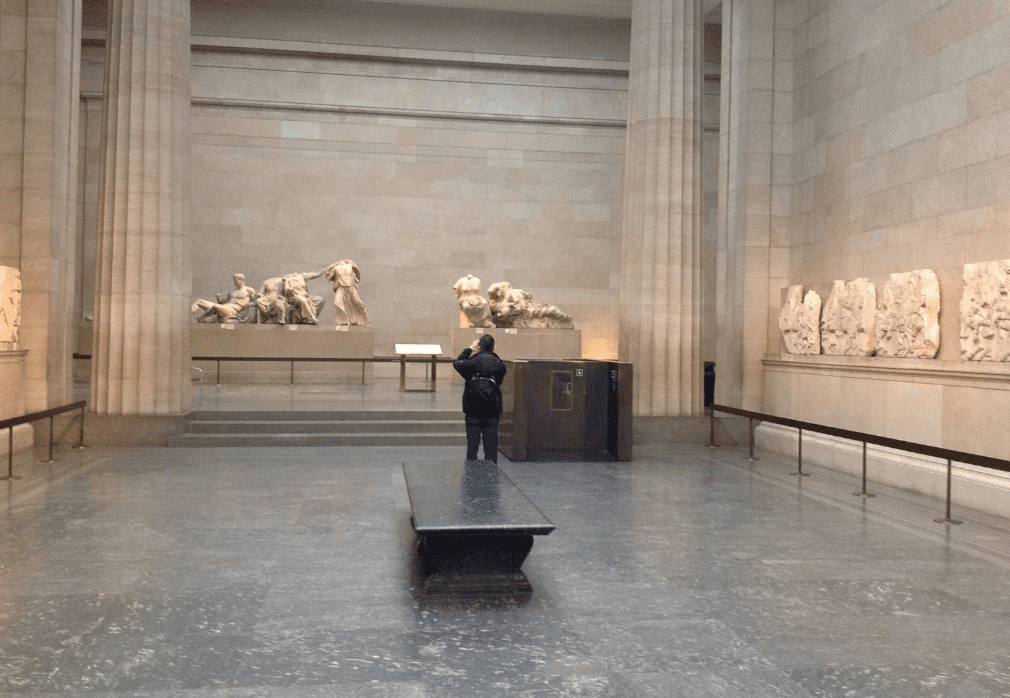

Dunveen Gallery

Today, the British Museum continues to be synonymous with the very best in world collections. The Norman Foster-designed Great Court, which opened in 2000 to a mixture of delight and controversy, is as bold and immediately iconic as any similar museum building in the world, immediately meaning that any idea of resting on laurels has to be forgotten. And the blockbuster exhibitions, drawing in both record crowds and much-needed revenue, continue to be hugely popular; the recent ‘Life and Death in Pompeii and Herculaneum’, in particular, reported queues for hours and sold-out events give every sense of an institution at the peak of its powers.

The British Museum

A great deal of the credit for its success must go to its visionary former director Neil MacGregor, who was largely responsible for championing it on the world stage and ensuring that it was often a step ahead of its rivals. His departure in 2015 led to a mixture of acclaim and mourning, but his replacement by Hartwig Fischer, the former director of the Dresden State Art Collections, has attracted a similar level of interest, although the jury is still out on whether Fischer – the first non-British director of the museum – will have MacGregor’s blend of crowd-pleasing chutzpah and serious academic qualities. However, both Fischer and MacGregor know that, over two and a half centuries after its foundation, the British Museum is far greater than any one man, be it king, director or visitor.

Instead, it continues to challenge, to stimulate and to delight. Long may this progress thrive.

Natasha Syed is the dynamic Editor-in-Chief of British Muslim Magazine, the UK’s premium Travel & Lifestyle publication catering to Muslim audiences. With a passion for storytelling and a keen eye for celebrating diverse cultures, she leads the magazine in curating inspiring content that bridges heritage, modern luxury, and faith-driven experiences.

Under her leadership, British Muslim Magazine continues to set the standard for authentic, and engaging trusted narratives, making it the go-to source for Muslim traveler's and lifestyle enthusiasts across the UK and beyond.